Introduction

Badger is an optimizer specifically designed for Accelerator Control Room (ACR). It's the spiritual successor of Ocelot optimizer.

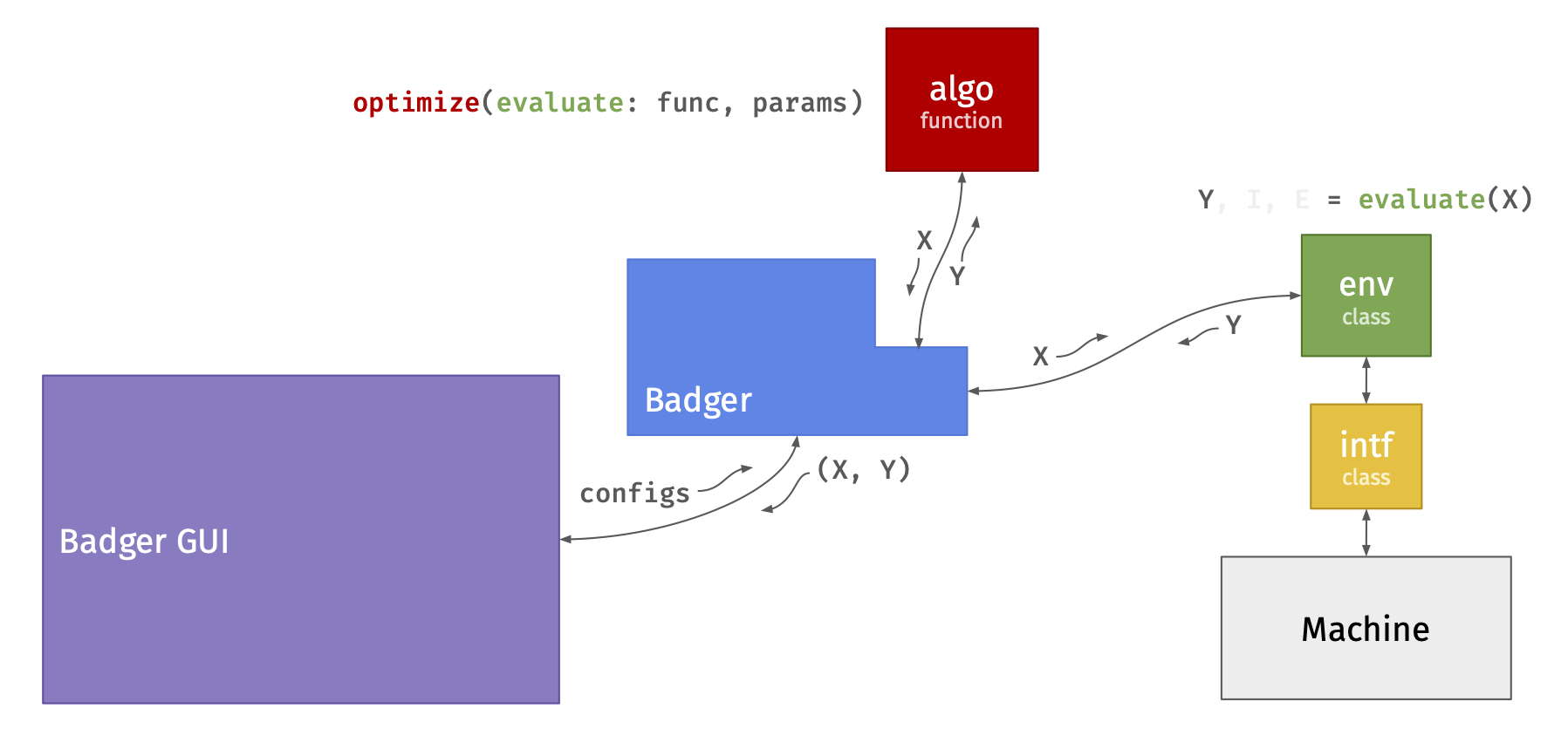

Badger abstracts an optimization run as an optimization algorithm interacts with an environment, by following some pre-defined rules. As visualized in the picture above, the environment is controlled by the algorithm and tunes/observes the control system/machine through an interface, while the users control/monitor the optimization flow through a graphical user interface (GUI) or a command line interface (CLI).

Algorithms, environments, and interfaces in Badger are all managed through a plugin system, and could be developed and maintained separately. The application interfaces (API) for creating the plugins are very straightforward and simple, yet abstractive enough to handle various situations.

Badger offers 3 modes to satisfy different user groups:

- GUI mode, for ACR operators, enable them to perform regular optimization tasks with one click

- CLI mode, for the command line lovers or the situation without a screen, configure and run the whole optimization in one line efficiently

- API mode, for the algorithm developers, use the environments provided by Badger without the troubles to configure them

Important concepts

As shown in the Badger schematic plot above, there are several terms/concepts in Badger, and their meaning are a little different with regard to their general definitions. Let's briefly go through the terms/concepts in Badger in the following sections.

Routine

An optimization setup in Badger is called a routine. A routine contains all the information needed to perform the optimization:

- The optimization algorithm and its hyperparameters

- The environment on which the optimization would be performed

- The configuration of the optimization, such as variables, objectives, and constraints

To run an optimization in Badger, the users need to define the routine. Badger provides several ways to easily compose the routine, so no worries, you'll not have to write it by hands:)

Interface

An interface in Badger is a piece of code that talks to the underlying control system/machine. It communicates to the control system to:

- Set a process variable (PV) to some specific value

- Get the value of a PV

An interface is also responsible to perform the configuration needed for communicating with the control system, and the configuration can be customized by passing a params dictionary to the interface.

The concept of interface was introduced to Badger for better code reuse. You don't have to copy-n-paste the same fundamental code again and again when coding your optimization problems for the same underlying control system. Now you could simply ask Badger to use the same interface, and focus more on the higher level logic of the problem.

Interfaces are optional in Badger -- an interface is not needed if the optimization problem is simple enough (say, analytical function) that you can directly shape it into an environment.

Environment

An environment is Badger's way to (partially) abstract an optimization problem. A typical optimization problem usually consists of the variables to tune, and the objectives to optimize. A Badger environment defines all the interested variables and observations of a control system/machine. An optimization problem can be specified by stating which variables in the environment are the variables to tune, and which observations are the objectives to optimize. Furthermore, one can define the constraints for the optimization by picking up some observation from the environment and giving it a threshold.

Take the following case as an example. Assume that we have an accelerator control system and we'd like to tune the quadupoles QUAD:1, QUAD:2 and minimize the horizontal beam size on a screen BSIZE:X. We also want to keep the vertical beam size BSIZE:Y below a certain value. To do this in Badger, we could define an environment that has variables:

QUAD:1QUAD:2

And observations:

BSIZE:XBSIZE:Y

Then define a routine config to specify details of the optimization problem, as will be mentioned in the next section.

One environment could support multiple relevant optimization problems -- just put all the variables and observations to the environment, and use routine config to select which variables/observations to use for the optimization.

Routine config

A routine config is the counterpart of optimization problem abstraction with regard to environment. An optimization problem can be fully defined by an environment with a routine config.

On top of the variables and observations provided by environment, routine config tells Badger which and how variables/observations are used as the tuning variables/objectives/constraints.

Use the example from the last section, the routine config for the problem could be:

variables:

- QUAD:1

- QUAD:2

objectives:

- BSIZE:X: MINIMIZE

constraints:

- BSIZE:Y:

- LESS_THAN

- 0.5

The reasons to divide the optimization problem definition into two parts (environment and routine config) are:

- Better code reuse

- Operations in ACR usually require slightly changing a routine frequently, so it's good to have an abstraction for the frequently changed configurations (routine config), to avoid messing with the optimization source code

Features

One of Badger's core features is the ability to extend easily. Badger offers two ways to extend its capibility: making a plugin, or implementing an extension.

Plugin system

Algorithms, interfaces, and environments are all plugins in Badger. A plugin in Badger is a set of python scripts, a YAML config file, and an optional README.md. A typical file structure of a plugin looks like:

|--<PLUGIN_ID>

|--__init__.py

|--configs.yaml

|--README.md

|--...

The role/feature of each file will be discussed in details later in the create a plugin section.

One unique feature of Badger plugins is that plugins can be nested -- you can use any available plugins inside your own plugin. Say, one could combine two environments and create a new one effortlessly, thanks to this nestable nature of Badger plugins. You could explore the infinity possibilities by nesting plugins together with your imagination!

Extension system

Extension system is another way to extend Badger's capabilities, and in a sense it's more powerful than the plugin system, since it could make a batch of existing algorithms available in Badger in a few lines of code!

Let's assume that we already have an optimization platform/framework that provides a dozen of algorithms, and we'd like to use these algorithms to optimize on our machine environment. One way to do that is porting all these algorthms to Badger through the plugin system, and use Badger to perform the optimization. Extension system was designed just for this situation, since porting the algorithms one by one is tedious and inefficient. Extension system provides the APIs that are required to be implemented in order to "port" all the algorithms of another optimization framework/platform in one go. More details about extension system can be found in the implement an extension section.

With the extension system, Badger could use any existing algorithms from another optimization package. Currently, Badger has the following extensions available:

And more extensions are on the way (for example, teeport extension for remote optimization)!